Two Sets of Books: The SBA 504 Documents

Court-ordered discovery in Inspirador v. Southwestern Business Finance Corp. revealed CDC President Robert D. McGee coordinated false SBA certifications understating loan amounts by $250,000, enabling $1M+ equity extraction from a profitable business cleared by federal investigators.

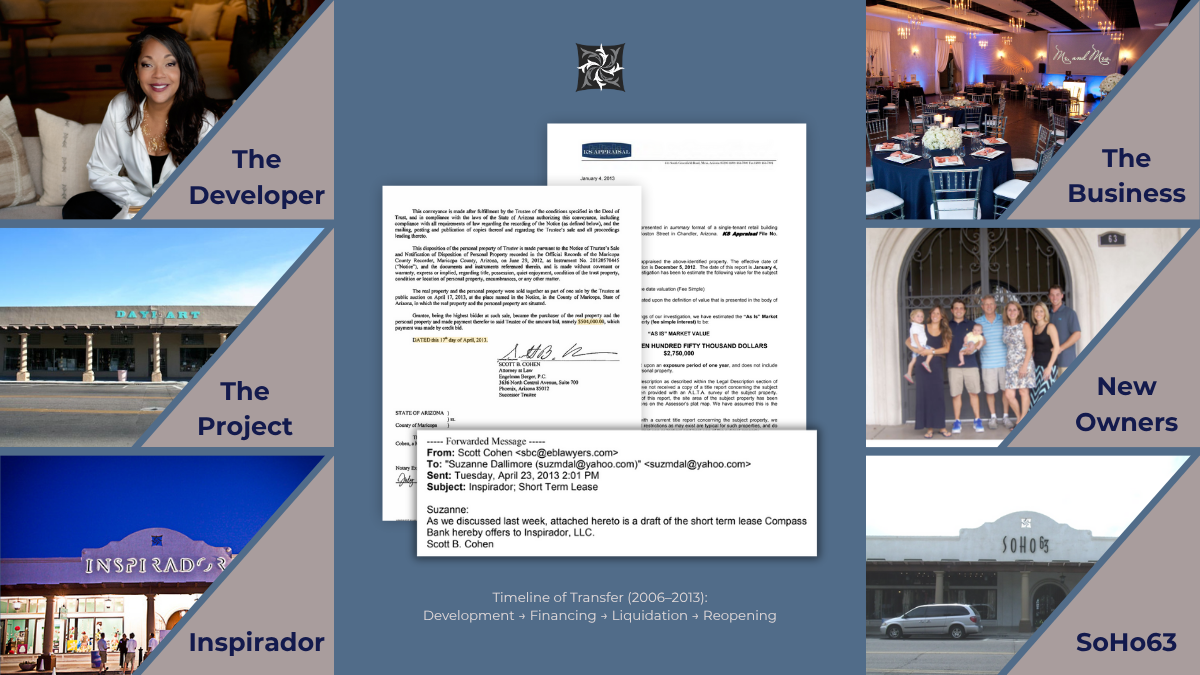

In 2006, entrepreneur Dilia Wood secured an SBA 504 loan to restore a historic building at 63 East Boston Street in Chandler, Arizona. The adaptive reuse project—Inspirador—became a profitable event venue. By 2013, it had been transferred at trustee sale to new owners who reopened it as SoHo63. What follows is the documented timeline showing how systematic extraction works when self-certification meets strategic timing.

Most people think car thieves want the car.

They don't. They want what's inside it—the catalytic converter, made of platinum, worth more than gold. A skilled thief can extract it in ninety seconds with a battery-powered saw. The car? Left on blocks, worthless without the component that made it run.

Robert D. McGee—CDC president of Southwestern Business Finance Corporation for 19 years, known to everyone as "Bob" (he signed it with quotation marks)—understood the same principle about small businesses. You don't steal the building. You extract the business inside: the cashflow, the established customer base, the operational systems that generate revenue long after real estate transactions close. A turnkey operation is worth more than any static asset. It's platinum.

And if you know how to control timing—when documents flow, when pressure mounts, when questions get asked—you can extract it while appearing to follow every rule.

McGee spent nineteen years perfecting the extraction. Not through fraud that looked like fraud—that gets investigated. Through precision that looked like compliance. By the time anyone noticed, the platinum was gone and the paperwork was perfected.

This isn't speculation. It's documentation.

In 2012, court-ordered discovery revealed seven years of coordinated extraction: false certifications, manufactured allegations, and strategic timing that weaponized the single phrase relevant to every SBA loan agreement:

"Time is of the essence."

In SBA lending, that phrase creates urgency. Miss a deadline, delay a submission, raise a question at the wrong moment—the entire loan structure can collapse. For borrowers, it's pressure. For McGee, it was leverage. By orchestrating exactly when information appeared (and when it didn't), he could keep borrowers reactive, lenders compliant, and the SBA satisfied—all while building toward systematic transfer.

What follows is the timeline and evidence showing how three mechanisms worked together over seven years to extract equity from a profitable business—not through default, but through precision.

The Three Mechanisms

Like that catalytic converter theft, extraction requires three independent systems:

1: Self-Certification: CDCs report loan amounts without submitting recorded documents—allowing two realities to exist.

2: "Adverse Change" Manipulation: Protective provisions weaponized through manufactured allegations filed in systems borrowers cannot access.

3: Timing Control: Strategic pressure using the SBA's own urgency against borrowers—"time is of the essence" as leverage.

Timing wasn't just one of the three mechanisms. It was the spine that held them together.

By 2013, the property had been acquired at trustee sale and continues operating profitably today—validating that the business model was sound and the transfer was systematic, not the result of market failure.

What McGee extracted wasn't a building. It was seven years of equity built through restoration—the platinum inside the business that kept generating value long after the original owner was gone.

Table of Contents

The Story

- The Timeline — Seven Years of Orchestrated Extraction (2006-2013)

The Evidence

- The Trap — Authorization Language That Removed Borrower Optionality (2006)

- The Discrepancy — Recorded Reality vs. Reported Reality (2006-2007)

- The Pattern — Repetition Establishes Intent (2007-2008)

- The Coordination — Internal Emails Confirm Timing Control (2008)

- The Cover — Manufacturing "Adverse Change" (February 2008)

- The Incentive — The $1 Million Surplus (2008)

- The Transfer — The Controlled Liquidation (2013)

Findings & Implications

- For SBA 504 Borrowers — What I Would Do Differently

- For the SBA 504 Program — Structural Reform and Administrative Feasibility

- For Investigative Journalists — Indicators of Systemic Extraction

- The 2025 Question — Verification vs. Efficiency

Reference

- The Aftermath — What Happened to the CDC, Whistleblower, and Borrower

- Source Documents — Access Timeline & Court-Ordered Discovery

- Rights & Permissions

THE TIMELINE

The orchestration spanned seven years. Each date mattered.

2006: The Foundation

- June: CDC pre-approval: borrower "MAY" use $250,000 city grant

- September: SBA Authorization revised: borrower "HAS used" $250,000 grant—obligation created before funds existed

- November: Property purchase and construction begins at 63 East Boston Street, Chandler, AZ

Total Project Costs $2,079,600 (Original)

● 50% | Bank Loan #1 (Permanent) — $1,039,900

● 30% | Bank Loan #2 (Bank Construction → SBA/CDC Buyout) — $579,700

● 20% | Borrower Contribution — $460,000 cash

(Special Loan Condition: City of Chandler Grant of $250,000 "must be used half for monthly loan payments and half for working capital needs.")

2007: The Modification

- March 14: Construction halted—roof damage discovered. Bank and CDC notified of cost overruns.

- April 25: Loans increased to cover repairs. Loan #1 modified to $1,400,000 (recorded with county). Borrower contributes additional $50,000. Construction resumes.

- May: CDC reports to SBA: Loan #1 = $1,150,000 (eliminates borrower's additional $50,000)—first false certification

- May-October: Pattern of false certifications continues across multiple SBA submissions

- October: Project complete. Certificate of Occupancy issued. Business opens as Inspirador event venue.

Total Project Costs $2,600,000 (Modification)

● 50% | Bank Loan #1 (Permanent) — $1,039,900⇒$1,400,000

● 30% | Bank Loan #2 (Bank Construction → SBA/CDC Buyout) — $579,700⇒$690,000

● 20% | Borrower Contribution — $460,000 cash⇒$510,000

(Special Loan Condition unchanged: City grant of $250,000 still tied to loan payment/working capital requirement)

REPORTED TO SBA:

Loan #1 = $1,150,000 ($250,000 understatement)

2008: The Manufactured Crisis

Business Status: Inspirador operational and profitable. All payments current.

- January 22: $250K city grant awarded to developer

- January 22: McGee submits Funding Letter for debenture bond sale, March 12 funding date. Certifies "no adverse change" and "no misleading information"

- February 8: McGee and bank demand borrower "hand over" $250K grant to pay down Loan #1. Borrower refuses.

- February 11: McGee cancels March 12 funding date (72 hours after refusal)

- February 28: McGee files confidential fraud referral with SBA OIG—13 days before bond market deadline

- February 29: SBA responds within 24 hours: "Please discontinue all actions or contact until notified by an OIG agent." McGee immediately notifies bank, citing SBA directive as reason to halt buyout. Borrower not notified.

- March: Bank appraisal: $2,900,000 | Actual LTV: 72% | Reported LTV: 63%

- March 12: Original bond sale date—buyout permanently canceled

- April 8: SBA confirms allegations constitute "adverse change" sufficient to cancel loan permanently (no investigation warranted)

2009-2011: The Coordination

Business Status: Inspirador continues operating profitably under 3-year balloon structure.

- Bank and CDC coordinate property appraisals (joint names on reports)

- False liens and fraud allegations remain on federal records—preventing refinancing

- Litigation begins exposing the false certification pattern

- 3-year balloon countdown continues—expires January 2012

2012: The Clearing

Business Status: Profitable, all payments current, restoration complete.

- June: Congressional intervention forces SBA OIG to reopen investigation

- July: SBA OIG concludes: "There is no basis to proceed with either a civil or criminal fraud investigation." Borrower and whistleblower cleared.

- Fabricated liens removed from public records

- Federal refinancing becomes possible for the first time in four years

2013: The Transfer

Business Status: Profitable, all payments current, federal rescue underway.

- January: U.S. Department of Commerce's Minority Business Development Agency standing by to refinance. Formally requests court pause foreclosure: "This foreclosure will not only complicate the refinancing, it will put undue pressure to our lenders."

- January 31: 3-year balloon note expires (date written in 2008)

- Bank refuses to extend term or cooperate with federal refinancing

- April 17: Trustee sale. Property appraisal: $2.75M. Winning bid: $504,000. One bidder.

- August: Building reopens as SoHo63 under new ownership

- October 17: Robert D. McGee announces retirement from Southwestern Business Finance Corporation

The gap between 2006 and 2013 wasn't passive time. It was controlled orchestration.

THE EVIDENCE

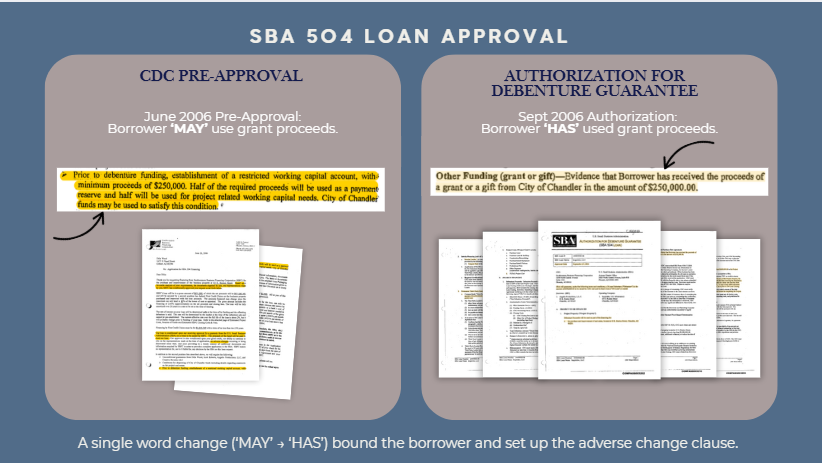

2006 — THE TRAP: The Authorization Language That Removed Borrower Optionality

The first documented manipulation occurred in the loan’s foundational paperwork. Between the preliminary CDC approval and the final SBA authorization, a single word change altered the borrower’s rights and obligations regarding a $250,000 city grant.

That change removed the borrower’s discretion over how the grant could be used, setting up a condition that would later enable an “adverse change” finding no matter what the borrower did.

The Language Shift

June 2006 – CDC Pre-Approval

“Borrower may use $250,000 city grant proceeds for working capital.”

September 27, 2006 – SBA Authorization for Debenture Guarantee #24404960-08

“Borrower has used $250,000 city grant proceeds for working capital.”

Effect:

This revision removed the borrower’s optionality and embedded a presumption of use. It required that the grant be applied exactly as stated—half toward loan repayment and half toward working capital—despite the grant funds not yet being awarded. Once inserted into the SBA’s official file, this phrasing could later be invoked to allege “misleading information” or “adverse change,” regardless of the borrower’s actual compliance.

How the Trap Worked

- If the borrower followed the instruction and applied the grant to pay down the loan, the act itself constituted a material alteration of the capital structure—creating an adverse change and violating the terms of approval.

- If the borrower refused, waiting for proper disbursement or use of funds, the CDC could later claim the borrower had misrepresented the use of grant proceeds—also an adverse change.

- Either decision produced a technical breach that preserved the CDC’s leverage and future justification for cancellation.

The trap was not in a missing payment or a failed business. It was embedded in the loan’s language—engineered optionality converted into a no-win condition that could be activated at will.

Supporting Evidence

- CDC Pre-Approval Memorandum, June 2006 (Exhibit A)

- SBA Authorization for Debenture Guarantee #24404960-08, Sept 27 2006 (Exhibit B)

This initial revision of a single word transformed a flexible funding clause into a structural tripwire—one that would later define the borrower’s entire relationship with the lender and the SBA.

Note: The alteration from “may” to “has” converted a discretionary grant condition into a binding obligation. This language shift created a built-in compliance trigger—an “adverse change” condition that could be invoked at any time.

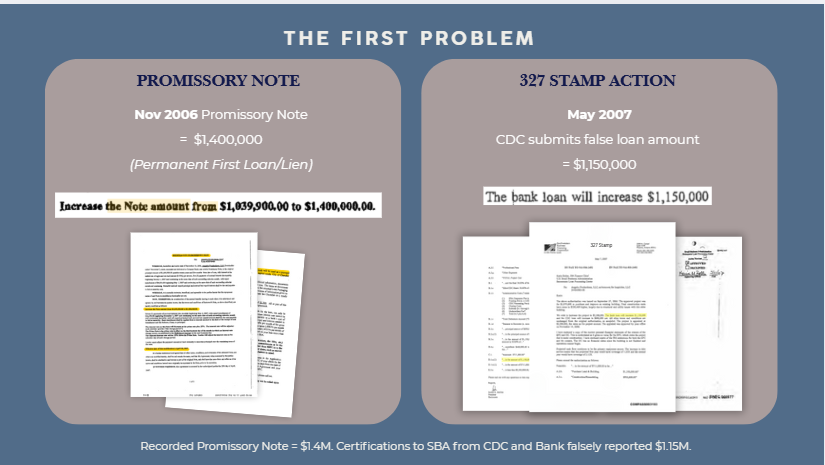

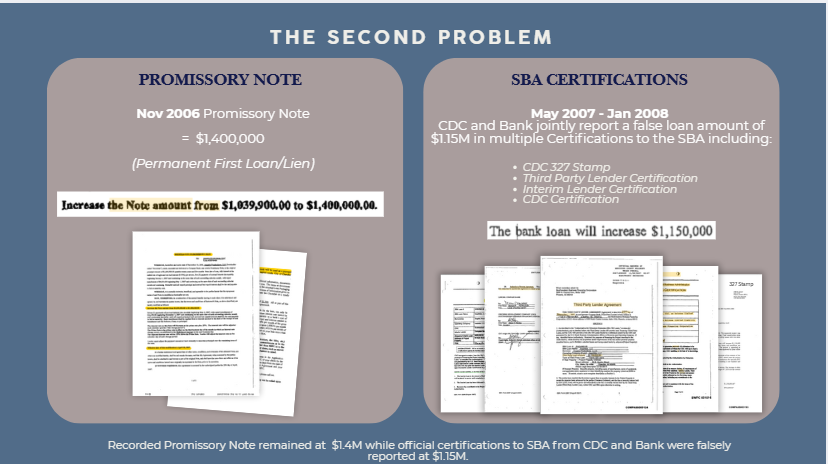

THE DISCREPANCY (2006-2007): Recorded Reality vs. Reported Reality

Two Loans. Two Sets of Books.

- Loan #1 (Bank Permanent — first-position lien) – documented by a Promissory Note recorded with the county.

- Loan #2 (Bank Construction → SBA/CDC Takeout — second-position) – interim/construction financing to be taken out by the SBA debenture.

By November 2006, purchase and construction financing for 63 E. Boston were in place under a standard 50/30/20 SBA 504 structure. In April 2007, after storm damage, both loans were increased to cover repairs. The first-position note (Loan #1) was modified and recorded at $1,400,000. The borrower contributed an additional $50,000, bringing borrower cash to $510,000.

What the SBA saw was different.

In May 2007, the CDC submitted a 327 Action to SBA reporting Loan #1 at $1,150,000 and Borrower Contribution at $460,000. Borrowers do not receive 327 filings; they circulate only between CDC and SBA. For eight months, the lower figures propagated through SBA systems while the higher, accurate figures remained in county records.

Why it mattered

- No Preference (Third Party Lender Agreement / 13 C.F.R. §120.10)

First-lien lenders cannot improve their position or receive preference without prior written consent of CDC/SBA. Understating Loan #1 in federal filings while carrying a higher recorded note effectively concealed a first-lien advantage and any related changes. - “Not Misleading” Certifications

Lenders must disclose all material information so certifications are not misleading. Reporting $1.15M to SBA while the borrower was obligated on a $1.4M recorded note is a material under-statement. - SBA review trigger

Accurate figures would have flagged the capital changes. SBA would have required justification for any effective shift toward a 30% borrower share (or equivalent capital inflows) before approving a takeout. Concealment avoided that scrutiny.

Math Audit

Recorded Reality (County Records & Executed Note)

• Total Project Cost: $2,600,000

• Loan #1 (Permanent Note): $1,400,000

• Loan #2 (Construction → SBA Takeout): $690,000

• Borrower Cash Contribution: $510,000 ($460K + $50K additional)

Reported to SBA (CDC 327 Action, May 2007)

• Total Project Cost: $2,300,000

• Loan #1 Reported: $1,150,000

• Borrower Contribution Reported: $460,000

Discrepancy

• Total Project Cost Understated by $300,000

• Loan #1 Understated by $250,000

• Borrower Cash Understated by $50,000

Result: $300,000 in concealed capital and a paper trail that hid unapproved changes from the SBA.

Effect: The altered capital structure made the deal look cheaper, the bank’s first-lien exposure smaller, and the borrower’s equity unchanged—avoiding SBA red-flag review and preserving a paper trail that could later be used to allege “adverse change.”

Supporting Evidence

- Recorded Promissory Note / Modification (Loan #1 = $1,400,000) — April 25, 2007

- CDC 327 Action to SBA (Loan #1 reported = $1,150,000; Total Project = $2,300,000; Borrower = $460,000) — May 2007

Supporting Documents Referenced

- CDC Certification (“No Adverse Change” and “No Misleading Information”)

- Third Party Lender Agreement (“No Preference”)

- Interim / Third-Party Lender Certification Clause (“…not misleading.”)

Note: The $300,000 understatement—spread across loan, project cost, and borrower contribution—made the transaction appear compliant on paper while concealing unapproved capital shifts that would have required SBA review.

2007–2008 — THE PATTERN: Repetition Establishes Intent

The Repeated Discrepancy

The $250,000 understatement was not a single error.

Between May 2007 and January 2008, McGee’s CDC and the participating bank submitted multiple certifications to the SBA—each reporting Loan #1 as $1,150,000 instead of the recorded $1,400,000.

The same figure appeared consistently in:

- CDC 327 Stamp Actions

- Third-Party Lender Certifications

- Interim Lender Certifications

- CDC Final Certification

The false amount was repeated across filings, correspondence, and even in later fraud-referral documentation and court records.

It was never corrected.

The Scope of False Reporting

McGee’s CDC not only understated Loan #1 by $250,000, but also omitted the borrower’s additional $50,000 cash contribution from all certifications—a total of $300,000 in concealed obligations.

Each misstatement reduced the apparent project cost and risk exposure while increasing the potential surplus recoverable upon liquidation.

Every document included signed attestations that:

“No misleading information has been provided to the SBA,” and

“No adverse change has occurred in the borrower’s financial condition.”

Meanwhile, the recorded Promissory Note remained at $1.4 million.

The business was fully operational, and all payments were current.

Yet in the SBA’s internal records, the loan appeared $250,000 smaller—a phantom debt structure that did not match the borrower’s actual obligations.

The Information Gap

Borrowers do not receive copies of CDC or bank certifications submitted to the SBA.

As a result, I continued making payments on a $1.4 million note while the SBA’s files reflected $1.15 million.

There was no direct channel to verify what was being reported on my behalf.

The system functioned on trust; that trust was the vulnerability.

For eight months, each certification reaffirmed the same false data.

By the time those figures entered the bond market in March 2008, the pattern had become institutionalized within SBA systems—making later correction or intervention nearly impossible without exposing prior misrepresentations.

Supporting Evidence

- CDC 327 Action Reports (May 2007 – Jan 2008) showing $1.15 M certification

- Third-Party, Interim, and Final Lender Certifications (2007–2008)

- Recorded Promissory Note – $1.4 M (County Record)

- CDC and bank attestations citing “no misleading information” / “no adverse change” clauses

Note: Repetition transforms an error into a system pattern. Each certification reaffirmed the same misrepresentation, creating a consistent but false record of borrower obligations across every level of SBA review.

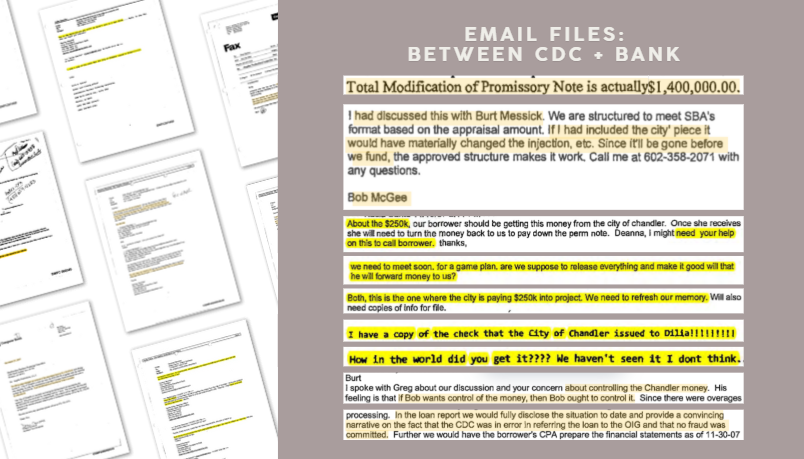

2008 — THE COORDINATION: Internal Emails Confirm Timing Control

The Communications

Internal correspondence between CDC President Robert D. McGee and bank officials reveals coordinated awareness of the discrepancies and deliberate timing of the SBA buyout cancellation.

“Total modification of Promissory Note is actually $1,400,000.00.”

— Bank acknowledging the true loan amount while certifying $1.15 M to the SBA

“We need to meet soon, for a game plan.”

— Email between lenders coordinating next steps

“Don’t worry about the city piece… since it’ll be gone before we fund.”

— CDC president assuring bank that the $250 K city grant would be removed before SBA funding

“How in the world did you get it???? We haven’t seen it I don’t think.”

— Reaction when borrower obtained internal documentation assumed to remain undisclosed

Each message appeared routine in isolation.

Together, they demonstrated awareness of the false figures, joint timing control, and a shared strategy to prevent discovery until after the loan had passed through certification and bond processes.

Pattern of Communication

McGee’s emails reflected calculated neutrality—language that, viewed individually, maintained plausible deniability.

Phrases such as “game plan,” “before we fund,” and “don’t worry about the city piece” appeared innocuous but, when sequenced, aligned precisely with key certification and funding dates identified in SBA records.

No explicit instruction was given to falsify; the coordination resided in timing, framing, and silence.

Borrower Exclusion

The borrower was intentionally excluded from correspondence.

Internal recipients included CDC officers, bank executives, and appraisers—never the borrower.

All decisions affecting the project’s financial standing occurred through private channels inaccessible to the borrower or the SBA loan monitoring system.

By the time the borrower obtained fragments of these communications, the misreporting had already been embedded in federal systems.

The Bank’s Role

When McGee canceled the SBA buyout in early 2008, the bank did not pursue collection or legal enforcement.

Instead, it converted the $690,000 construction loan into a three-year balloon note—matching the term McGee required to time the liquidation window.

Appraisal reports from the same period listed both the bank and CDC as co-clients, confirming shared valuation oversight.

Emails tracked appraisal coordination and property timing, illustrating that the bank was not a passive lender but a participant in establishing the valuations later used to justify the extraction.

The Countdown

The three-year balloon note became the countdown clock.

Each subsequent action—valuation updates, borrower correspondence, and internal status reports—aligned to that maturity date.

When the balloon expired in January 2012, the structure was in place: documentation synchronized, valuations established, and the property positioned for trustee sale.

Supporting Evidence

- Email correspondence between CDC and bank officials (2007–2008)

- 2008 appraisal reports listing CDC and bank as co-clients

- Bank loan modification converting $690 K interim loan to 3-year balloon note

- SBA certification records showing unchanged $1.15 M figure during same period

Note: The internal communications contain no explicit instructions to falsify information. Their evidentiary value lies in demonstrating: (1) awareness of the discrepancy, (2) coordination around key certification dates, and (3) deliberate borrower exclusion from decision-making.

February 2008 — THE COVER: Manufacturing “Adverse Change”

The Timing Problem

By February 2008, the false certifications had created a critical exposure point.

Those filings—each reflecting a $1.15 million first-lien amount—were scheduled to enter the SBA bond market in March 2008.

Once the debenture closed, the discrepancy between the certified and recorded amounts would become visible to federal reviewers.

McGee needed justification to cancel before the transaction reached that stage.

The Certification on File

With construction complete and the business fully operational, McGee’s CDC had already requested SBA debenture funding while certifying that:

“All material information known by CDC has been disclosed.”

“No misleading information has been provided to the SBA.”

Loan #1 amount: $1,150,000

The actual recorded amount was $1,400,000.

The Precision Strike

February 28, 2008 — Thirteen days before the bond market deadline

McGee filed a confidential fraud referral with the SBA Office of Inspector General (OIG), alleging borrower fraud based on a “suspicious balance sheet” generated by his own CDC during internal underwriting.

February 29, 2008 — Twenty-four hours later

The SBA OIG responded:

“Please discontinue all actions or contact until notified by an OIG agent.”

McGee immediately informed the bank:

“I have not notified either the borrower or her attorney. Per the SBA’s directive below, I am precluded from initiating any contact without pre-approval from the OIG.”

Within one day, McGee obtained formal authority to halt the buyout and explicit instruction not to contact the borrower.

The OIG directive provided procedural cover to stop funding without triggering breach-of-contract exposure.

April 8, 2008

The SBA confirmed that, while the OIG declined to investigate (no government funds had been disbursed or lost), the allegations constituted sufficient “adverse change” to permanently cancel the loan authorization.

No borrower notification.

No independent verification.

No investigation.

The result: a compliant cancellation, not a contested one.

The Countdown to Cancellation

| Date | Action | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Jan 22, 2008 | CDC requests SBA debenture funding | Certifies “no adverse change” and “no misleading information.” |

| Feb 8, 2008 | CDC and bank demand $250,000 grant paydown | Borrower refuses. |

| Feb 11, 2008 | CDC cancels funding request | Internal coordination continues. |

| Feb 28, 2008 | Fraud referral filed with SBA OIG | Alleging borrower fraud. |

| Feb 29, 2008 | SBA OIG orders “no contact” directive | Borrower not notified. |

| Mar 12, 2008 | Scheduled bond sale date | Permanently canceled. |

| Apr 8, 2008 | SBA confirms “adverse change” | Loan canceled in full. |

The Mechanism

In the SBA 504 process, “time is of the essence.”

Once a funding date is set, any certification or condition change must be reported immediately.

If a material “adverse change” is identified—such as alleged borrower misrepresentation—the CDC must suspend funding pending OIG review.

That procedural requirement became McGee’s tool of control.

By manufacturing an adverse change and invoking the OIG process, he converted a pending debenture into a compliant cancellation.

The Outcome

The fraud referral was not a risk; it was a protective mechanism.

It froze the transaction, insulated the CDC from liability, and preserved the ability to liquidate the asset later under the “no loss to government” framework.

The borrower was never informed that the loan had been canceled until after the opportunity for correction had expired.

The Counter-Investigation

In June 2012, the borrower and whistleblower jointly submitted a comprehensive evidence packet to the SBA Office of Inspector General through Arizona Congressman Jeff Flake, requesting the agency reconsider the February 2008 fraud referral with the complete documentary record McGee had concealed.

Working together, they assembled a detailed timeline and side-by-side comparison of recorded versus reported loan amounts. The whistleblower, as the CDC's former Business Development Officer of record on the loan, identified which specific certifications contained false reporting and provided the authenticated source documents proving the discrepancies.

The packet included:

- Timeline showing the 24-hour fraud referral response

- Original credit approval memos and Authorization for Debenture Guarantee

- CDC 327 Actions showing false $1.15M certifications

- Recorded Promissory Note modifications showing actual $1.4M amounts

- Internal emails coordinating the reporting discrepancy

- Evidence of McGee requesting the OIG fraud referral

Congressman Flake reviewed the evidence and forwarded it to the SBA on June 11, 2012, with a formal request for response.

Following the Congressional intervention, the SBA Office of Credit Risk Management invited the borrower to SBA headquarters in Washington, D.C. on July 10, 2012, for a formal review. By July 17, 2012, the agency confirmed it would conduct an on-site review of Southwestern Business Finance Corporation.

A response letter to Congressman Flake from the SBA cleared both the borrower and the whistleblower, concluding: "There is no basis to proceed with either a civil or criminal fraud investigation."

The packet that cleared them is the same evidence base underlying this case study.

Supporting Evidence

- SBA OIG correspondence (Feb 28–29, 2008) initiating the “no-contact” directive

- CDC email to Compass Bank referencing that directive: “precluded from initiating contact”

- SBA confirmation letter (Apr 8, 2008) — “Adverse change sufficient to cancel loan”

- CDC and bank certification records filed Jan 2008 showing $1.15 M reported versus $1.4 M recorded

- These same documents were later included in the 2012 congressional evidence packet that led to the SBA OIG’s clearance of both the borrower and the whistleblower

Note: The timing of the February 2008 fraud referral—thirteen days before the scheduled bond sale—and the 24-hour OIG response created procedural cover to halt funding without triggering breach-of-contract exposure.

The action satisfied SBA reporting requirements while obscuring the certification discrepancies that prompted it, a gap later corrected through the 2012 congressional submission.

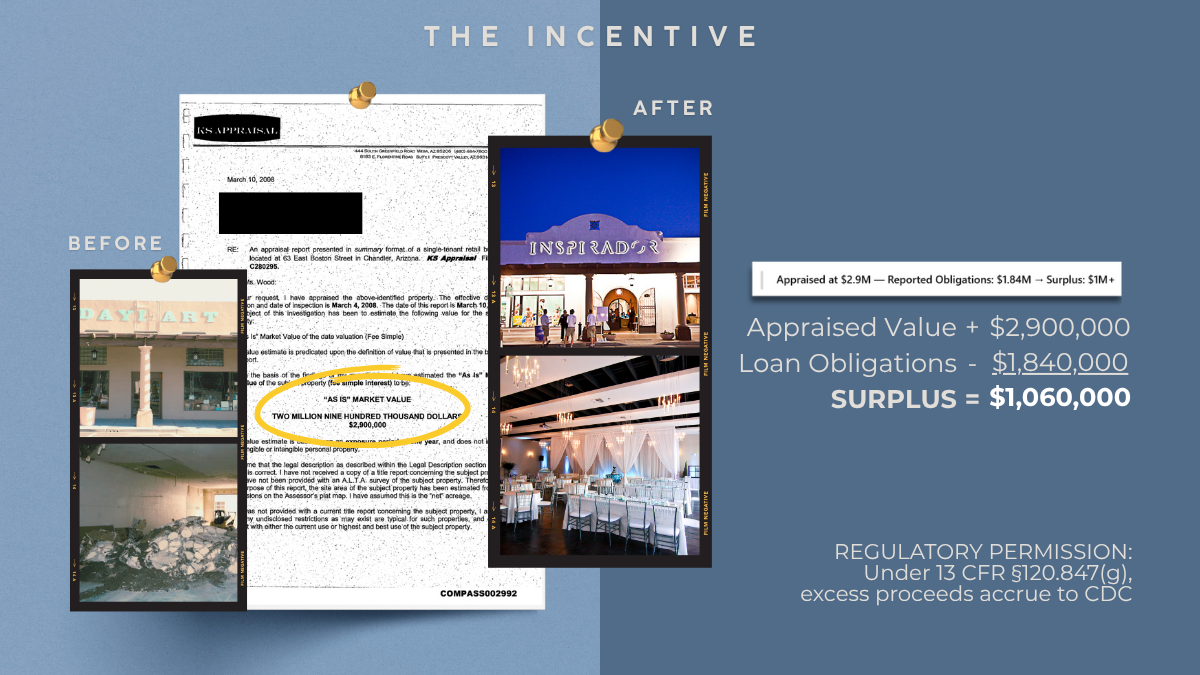

2008 — THE INCENTIVE: The $1 Million Surplus

The Valuation

By March 2008, the renovated property at 63 E. Boston Street carried a bank-approved appraisal of $2,900,000.

According to CDC filings, total reported obligations were $1,840,000:

- Loan #1 (reported): $1,150,000

- Loan #2 (SBA debenture): $690,000

Potential surplus at fair market liquidation: $1,060,000+

The Regulatory Framework: 13 CFR §120.847(g)

Under federal regulation, Certified Development Companies (CDCs) in the Premier Certified Lenders Program must maintain a Loan Loss Reserve Fund equal to 1% of each debenture and reimburse the SBA for 10% of any confirmed loss.

Once those minimums are satisfied, any excess liquidation proceeds—including surplus equity—accrue to the benefit of the CDC.

CDCs may withdraw excess funds upon SBA verification that required reserves remain intact.

Effect: A liquidation at appraised value against reported obligations would produce over $1 million in recoverable surplus. The SBA would record zero government loss. The transaction would appear fully compliant.

Why False Reporting Increased the Extractable Amount

Actual obligations (recorded):

- Loan #1: $1,400,000

- Loan #2: $690,000

- Total: $2,090,000

Reported obligations (to SBA):

- Loan #1: $1,150,000

- Loan #2: $690,000

- Total: $1,840,000

By understating Loan #1 by $250,000, the CDC increased the calculable surplus by that same amount—transforming a $810,000 surplus into a $1,060,000 surplus.

The "Zero Loss" Reputation

Robert D. McGee's CDC maintained a reputation for "zero loss to the government"—not through conservative underwriting, but through precision in liquidation timing and reporting. Under the PCLP framework:

- Minimal downside risk: 10% exposure only if SBA confirms a loss

- Unlimited upside: Retention of verified excess proceeds when no loss is recorded

- Regulatory compliance: All actions appear consistent with 13 C.F.R. § 120.847(g) once documentation is synchronized

The higher the appraised value and the lower the reported obligations, the greater the recoverable surplus. Controlling the loan's classification, timing, and liquidation sequence becomes financially valuable.

The Grant Demand in Context

In February 2008, McGee demanded the borrower apply the $250,000 City of Chandler grant toward Loan #1. If the borrower had complied, that action would have:

- Altered the capital structure certified to the SBA (adverse change)

- Triggered first-payment default under SBA policy

- Required initiation of a Litigation and Liquidation Plan

- Converted a performing loan into a controlled liquidation event

Refusal to comply gave McGee justification to file the confidential fraud referral. Either outcome served the extraction strategy.

Note: Retaining liquidation surplus is expressly permitted under federal regulation. The fraudulent conduct was the false reporting used to inflate that surplus and the manufactured adverse change used to force liquidation of a performing loan.

Supporting Evidence

- Bank Appraisal (March 2008): $2,900,000 valuation

- CDC certifications showing reported obligations of $1.84M

- 13 C.F.R. § 120.847(g) regulatory text

- Recorded Promissory Note showing actual $1.4M first lien

2013 — THE TRANSFER: The Controlled Liquidation

The Rescue Attempt

Through congressional oversight, the false allegations were cleared.

The fabricated liens—removed through litigation. Public scrutiny, including coverage by the Arizona Capitol Times, forced accountability.

The business continued to perform, with sold-out events and steady revenue. The restoration was complete. The enterprise was strong.

By early 2013, recovery was within reach.

January 2013:

A new appraisal valued the property at $2.75 million.

The bank claimed $621,000 remained on the second loan but refused to provide an accounting—stalling every refinancing attempt.

January 23, 2013:

Federal lenders under the U.S. Department of Commerce formally requested the court delay foreclosure, citing active efforts to refinance and reinstate the original loan.

“This foreclosure will not only complicate the refinancing—it will put undue pressure on our lenders.”

— David De Leon, Director of Finance, U.S. Department of Commerce

The government recognized the project’s viability and the harm a premature sale would cause.

The property stood on the threshold of rescue.

The Final Mechanism: Timing

But McGee’s final mechanism—timing—remained active.

When the SBA buyout was canceled in 2008, the bank had converted the interim construction loan into a three-year balloon note.

The note had since cycled twice through renewal extensions.

By January 2013, the balloon matured again—not due to default or missed payments, but solely because of the contractual date.

The bank, now under scrutiny for its coordination with the CDC, refused to extend or cooperate with the pending federal refinancing.

The court allowed foreclosure based on the balloon’s expiration date alone, even as the civil case exposing the CDC’s actions remained ongoing.

The Offer

At the point of sale, the bank extended one final proposal: Lease the property back. Continue operations under their control. Sign a confidentiality agreement.

Silence in exchange for survival.

The borrower refused.

The Trustee Sale

April 17, 2013 — Trustee sale, public auction.

- Appraised Value (2013): $2.75 million

- Winning Bid: $504,000

- Number of Bidders: One

By late August 2013, the building reopened under new ownership as SoHo63.

The new owners were a family with over twenty years in the event industry—operators of multiple businesses specializing in corporate logistics, meeting management, and wedding coordination.

In an interview with the East Valley Tribune, they described the purchase as “a perfect fit for our family of companies.”

“When the building came up as a foreclosure,” the new owner said, “we decided it was the perfect fit.”

The Result

- A profitable venue, cleared of legal obstacles, fully furnished and staffed, transferred at 82% below appraised value.

- A federally recognized rescue effort halted by procedural timing.

- A turnkey operation continuing under new ownership, identical in function and market position.

The cashflow Inspirador built did not fail.

Only its ownership changed hands.

The extraction was complete.

Ownership had changed hands at 82% below appraised value, days after federal agencies intervened to save it. The building sold for less than it cost to build, less than the down payment contributed, less than the monthly payments made over seven years.

It was a steal.

Supporting Evidence

- SBA OIG closure letter (July 2012) – “No basis to proceed”

- U.S. Department of Commerce letter requesting foreclosure pause

- Balloon Note maturity schedule and court filings (Jan–Apr 2013)

- Trustee Sale Record (Apr 17, 2013)

- Bank approved appraisal: $2.75 M

- East Valley Tribune interview (Aug 2013) – “Perfect fit for our family of companies”

The Choice

By April 17, 2013, ownership had transferred at 82% below appraised value to a single bidder positioned to operate the same business model Inspirador had built.

The bank’s offer was simple: lease back the property, sign a confidentiality agreement, and stay silent.

But silence was not for sale.

Note: The foreclosure occurred within days of federal intervention to refinance and preserve the business. Federal agencies stood ready to provide capital, but the balloon maturity date rendered their intervention procedurally impossible. The transaction transferred a profitable, operational enterprise—valued at $2.75 million—at 18 percent of appraised value to a single bidder with preexisting industry alignment.

Findings and Implications:

Understanding the Broader Impact of the Inspirador Case

This case exposed not a single act of misconduct, but a structural vulnerability inside the SBA 504 loan framework. What follows outlines the implications for borrowers, program administrators, journalists, and policymakers—and why this case still matters in 2025.

This isn’t only a story about one project or one borrower. It’s a record of how language, timing, and silence can transform public lending tools into private extraction mechanisms—all within regulatory compliance. What follows are the implications for those still working within that offering.

For SBA 504 Borrowers — The Human Impact of a Structural Flaw

For SBA 504 Borrowers — What I Would Do Differently

The SBA 504 program remains one of the best financing tools for commercial real estate.

It allowed me to acquire and restore a historic building—creating equity, community value, and a profitable business.

I wouldn’t be writing this if the program itself weren’t exceptional.

But I would approach it differently today.

Build Your Advisory Team First

Before signing anything, assemble your silent partner team—the experts you call before you call your lender.

Not the team in your business plan—the team behind it.

- A strategic CPA, not just for tax prep, but for reviewing financial statements before submission.

- A pre-vetted attorney with experience in complex commercial real estate and, ideally, federal loan programs.

- A mentor who’s closed deals of your scale and understands both financing and human behavior.

- A backup capital source—even unused, it’s leverage when timelines shift.

Your CDC has a loan committee. Your bank has underwriters.

Why shouldn’t you have an equivalent?

Consider keeping at least one advisor on monthly retainer.

When the stakes are high, access is insurance.

Know Your Partners

You’re investing 10–20% of total project costs—a substantial commitment.

Read your SBA Authorization for Debenture Guarantee in full.

Know who sits on the CDC’s loan committee, who its president is, and who approves modifications.

Interview your Business Development Officer and your bank representative.

Ask for references from borrowers who’ve closed similar-sized deals you can speak with directly.

If they deflect reasonable questions, that’s data.

Document Everything

From the first email, build your own archive.

Keep separate binders for each phase—pre-approval, construction, servicing.

After any verbal conversation, send a same-day recap email:

“For accuracy, here’s my understanding…”

That single sentence creates contemporaneous evidence.

The most common time for problems is after the first closing.

Watch for modification requests, “cost-saving” suggestions, or documents bearing signatures you didn’t produce.

When Something Feels Wrong

Escalate respectfully, in sequence, in addition to legal counsel:

- Business Development Officer

- CDC President

- SBA District Office

- SBA Office of Advocacy

- Office of the National Ombudsman

- Your Congressional representative

If someone claims an “adverse change,” ask for the exact document, action, or evidence that triggered it. Always maintain current, CPA-reviewed financials.

The Program Works

Most 504 loans close successfully. Most CDCs operate ethically.

This program enabled me to build something meaningful.

This case study documents an extraction—not to discourage participation, but to show what protection looks like versus what exploitation looks like.

The difference is transparency.

Good CDCs welcome questions.

Problematic ones deflect them.

Trust your instinct.

For the SBA 504 Program — Structural Reform and Administrative Feasibility

Trust but verify.

Reform doesn’t require a new law — just a new upload requirement.

The core vulnerability remains unchanged: CDCs self-certify loan data without attaching recorded documents for verification.

Recommended Reform

Require CDCs to attach digital copies of Promissory Notes, Deeds of Trust, and Modification Agreements to every certification submitted to the SBA.

- Administrative Cost: Minimal—uploading verified PDFs requires less effort than coordinating parallel records.

- Program Benefit: Eliminates the ability to sustain “two sets of books”: one recorded, one reported.

- Systemic Effect: Verification replaces assumption without sacrificing program efficiency.

For Investigative Journalists — Indicators of Systemic Extraction

The following forensic markers, derived from discovery in Inspirador v. Southwestern Business Finance Corporation (CV2011-081127), may signal broader patterns within the SBA 504 ecosystem:

1. Employee Implication Pattern

When a CDC alleges fraud by both the borrower and its own Business Development Officer, investigate further.

This dual-allegation structure:

- Creates “he said/she said” confusion officials often dismiss

- Provides plausible insider framing

- Silences key witnesses through professional retaliation

- May mask systemic extraction efforts

Red flag: The CDC proceeds with fraud referrals despite conflicting testimony or lack of proof.

2. The “No Government Loss” Catch-22

OIG declines investigation citing “no government funds lost,” while:

- Adverse-change cancellations proceed on unverified claims

- Borrowers lose equity

- SBA metrics report “zero loss”

This presents as risk-management success but reflects data manipulation.

3. Bankruptcy Burial

SBA 504 cases ending in bankruptcy often conceal discovery materials.

Court-ordered discovery in this case revealed:

- Certification discrepancies

- Timeline manipulation

- Repeated language in CDC fraud referrals

Investigate patterns where documentation “expired” or was destroyed under retention policies during active disputes.

4. Post-Extraction Continuity

Properties that continue operating profitably after distressed sale suggest:

- Sound business model

- Systematic transfer, not borrower failure

- Extracted equity disguised as market loss

Investigative priority: Identify CDCs showing repeated “zero-loss” reporting while borrowers lose equity or properties continue operating under new ownership.

The 2025 Question — Verification vs. Efficiency

In 2023, the SBA Office of Inspector General Report 23-09 documented over $200 billion in potentially fraudulent pandemic loans—17 percent of $1.2 trillion in PPP and EIDL disbursements.

Its finding:

“The agency weakened or removed the controls necessary to prevent fraudsters from easily gaining access to these programs.”

This case, from 2008, revealed the same flaw: self-certification without verification. The same mechanism that enabled pandemic fraud also enabled extraction within the 504 program.

The question isn’t whether the SBA 504 program has value. It does. Thousands of businesses have successfully built equity through this financing.

The question is whether self-certification without verification should remain the standard when the structure itself creates extraction pathways—when the same mechanisms that finance growth can be reversed to extract it.

Like a catalytic-converter theft, the extraction can happen in plain sight, following every procedural rule. By the time anyone notices the discrepancy, the platinum is gone. And the car is left on blocks.

THE AFTERMATH — What Happened to the CDC, the Whistleblower, and the Borrower

Upon McGee’s retirement, the Southwestern Business Financing Corporation (SBFC) board appointed Teresa Mandelin as President & CEO (inbusinessphx.com). Mandelin had served as Senior Vice President under McGee, overseeing loan operations and participating in modification approvals.

Internal emails produced in court-ordered discovery show Mandelin corresponding with McGee and Compass Bank officials on 2007 loan changes and certifications later determined to contain false reporting. In one message, she confirms:

“Bob and I reviewed and are okay with the changes.”

In another, she references initiating a “327 action” — the internal SBA process used to update loan records.

As of 2024, she continues to lead Pima Leasing & Financing Corporation, a Tucson-based firm active in SBA and economic-development lending (azbigmedia.com).

The whistleblower, Kevin Howard, was terminated and effectively blacklisted from the SBA lending industry.

The borrower lost the property, the business, and over $1 million in built equity, despite being cleared of all fraud allegations by the SBA Office of Inspector General.

The business continues operating profitably as SoHo63 under new ownership.

The regulatory framework remains unchanged. Self-certification without document verification is still standard practice in the SBA 504 program.

SOURCE ACCESS & RIGHTS

Source Documents & Access Timeline

Case Reference: Inspirador v. Southwestern Business Finance Corporation, Maricopa County Superior Court, Case No. CV2011-081127

Access Timeline

- February 7, 2011: McGee informs borrower that file access requires subpoena.

- December 2011: Litigation filed to obtain records and remove false liens.

- July 2012: SBA OIG clears borrower and whistleblower; fabricated liens removed.

- October 2012: Case sealed at McGee’s request to protect Kate Brophy McGee’s political campaign while she served as an Arizona State Representative. The court granted the motion despite the case involving potential fraud in a federally guaranteed loan program—raising questions about whether political considerations influenced public access to evidence of systematic extraction.

The sealing prompted Congressional inquiry and direct federal appeals, leading to SBA OIG intervention and borrower exoneration in July 2012.

Source Materials (Court-Ordered Discovery)

Available under NDA for verified journalistic review.

Primary Exhibits

- SBA Authorization for Debenture Guarantee

- CDC 327 Actions (2007–2008)

- Third-Party, Interim, and Final Lender Certifications

- Recorded Promissory Notes and Modifications (2006–2007)

- Fraud Referral and OIG Correspondence (2008)

- Balloon Note and Trustee Sale Records (2013)

Supporting Materials

- Internal CDC–Bank Email Correspondence (2007–2008)

- Appraisals listing CDC and Bank as co-clients

- U.S. Department of Commerce Letter to halt foreclosure (2013)

- Expert Witness Report — Marie McDonnell, CFE

- Whistleblower Statement — Kevin Howard, Former CDC BDO

Public Sources

- Arizona Capitol Times (Oct 4, 2012): “Lawsuit Sealed to Protect Rep. Kate Brophy McGee’s Campaign Amid Extortion Claims.”

- East Valley Tribune (Aug 2013): “Family Reopens Historic Chandler Venue.”

- SBA OIG Report 23-09 (June 27, 2023): COVID-19 Pandemic EIDL and PPP Loan Fraud Landscape.

Rights and Permissions

This report and supporting analysis are published for educational and journalistic review. All referenced court records are public domain.

Original commentary, annotations, and visual presentation © 2025 Dilia Wood.

For journalists and researchers: Source documents are available under NDA for verification or editorial use. Contact dw@diliawood.com for access.

For syndication or adaptation: Written consent is required for republication, dramatization, or documentary use.

For investigative partnerships: Full case files available to qualified news organizations and documentary producers. Serious inquiries only.

Legal Notice

This analysis reflects experience gained through litigation and document review, not legal training. All factual statements are supported by court records, sworn testimony, or official regulatory correspondence. Nothing in this article constitutes legal advice.

Related Documentation

63 East Boston Street: Historical Record — Complete development history and attribution record for 63 East Boston Street in Chandler, Arizona, documenting Dilia Wood's original development of Inspirador (2006-2013)

The Inspirador Story — First-person account of acquiring, financing, and developing 63 East Boston Street through SBA 504 financing

The Inspirador Case Study — Technical analysis of the adaptive reuse project at 63 East Boston Street